The Edict of Nantes

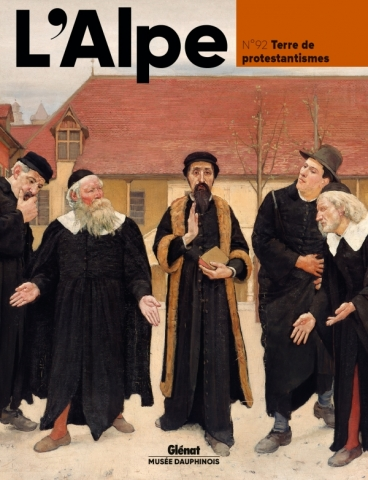

In the sixteenth century, France witnessed decades of strife between the established Catholic Church and the new Huguenot believers, followers of John Calvin’s Protestant doctrine. These culminated in a series of massacres in many parts of the country. The most horrible became known as the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572, at which thousands of Huguenots were killed in Paris. This triggered a massive wave of emigration; about 200,000 Huguenots fled France, to seek new homes in friendly countries.

King Henry IV – Good King Henry or Henry the Great – became King of France in 1589. Henry was baptised a Catholic but raised in the Protestant faith by his mother. As a Huguenot, he had been involved in the French Wars of Religion, barely escaping assassination in the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre. Henry IV initially kept the Protestant faith and fought against the Catholic League, which refused to accept a Protestant monarch. But after four years of military stalemate, he converted to Catholicism, reportedly saying, “Paris is well worth a mass.”

In 1598, King Henry IV issued the Edict of Nantes as an attempt to defuse the religious tensions. This established Catholicism as the state religion of France, but granted the Protestants equality with Catholics under the throne and a degree of freedom, thereby effectively ending the French Wars of Religion.

With the proclamation of the Edict of Nantes, pressure to leave France abated. However, enforcement of the Edict grew irregular and was increasingly ignored under Louis XIV, who became king in 1638. He imposed dragonnades and other forms of persecution for Protestants, which made life so intolerable that many fled the country. The Huguenot population of France dropped to 856,000 by the mid-1660s.

In 1685, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, causing panic among the Huguenots. Many again fled the country. The Channel Islands were a favourite stopping-off place, for several reasons: they were accessible even by small boats, French was spoken there, and they had strong Calvinist traditions.

See Calvinists.

3 Comments