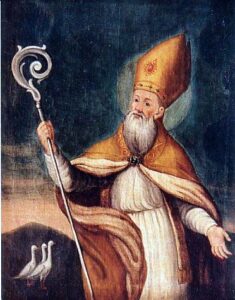

Why is Cerbonius shown with geese?

Cerbonius was a colourful character. I could describe him as a priest, a refugee, a hermit, a bishop, a bear-tamer, an animal-lover, a miracle-worker. He caused a sensation as a papal visitor, but the Roman Catholic Church later canonised him. I like to remember him for his intimate relationship with God. St. Gregory the Great described him in his Dialogues as “a man with a venerable life, who gave evidence of great holiness”.

Cerbonius was a colourful character. I could describe him as a priest, a refugee, a hermit, a bishop, a bear-tamer, an animal-lover, a miracle-worker. He caused a sensation as a papal visitor, but the Roman Catholic Church later canonised him. I like to remember him for his intimate relationship with God. St. Gregory the Great described him in his Dialogues as “a man with a venerable life, who gave evidence of great holiness”.

Early life

Cerbonius was born of Christian parents in Carthage, North Africa, in 493 AD, and ordained by Bishop Regulus. Persecution by the Arian Vandals caused the local Christian community to disperse. Together with Regulus and some priests, Cerbonius escaped to Italy. Some records date this flight ‘in the early 500s’, others suggest it was around 520 or 530 AD. A violent storm forced them to land in Tuscany, where they lived many years as hermits.

Cerbonius gained prominence after being chosen to become Bishop of Populonia (today’s Piombino) in 544 AD. He accepted this honour only reluctantly.

The people soon became frustrated with him, however. He celebrated mass every Sunday at daybreak, forcing his flock to get up in the middle of the night. “That’s when the angels sing in celebration of Jesus’s resurrection,” was his explanation.

Papal visit

Hearing the people’s complaints, Pope Vigilius summoned him to defend his behaviour. A manuscript in the Vatican library documents his trip to Rome. It records that the two legates sent to fetch him were dying of thirst on account of the heat. Cerbonius invoked God’s help. Suddenly, two deer approached and allowed themselves to be milked. Later in the journey, Cerbonius cured three men suffering from fever.

Hearing the people’s complaints, Pope Vigilius summoned him to defend his behaviour. A manuscript in the Vatican library documents his trip to Rome. It records that the two legates sent to fetch him were dying of thirst on account of the heat. Cerbonius invoked God’s help. Suddenly, two deer approached and allowed themselves to be milked. Later in the journey, Cerbonius cured three men suffering from fever.

On arrival at the Vatican hill, a flock of geese landed near Cerbonius. He ordered them not to leave until he had met with the Pope. The geese obeyed, and Cerbonius later dismissed them with the sign of the cross, to the amazement of those present. For this reason, pictures of Cerbonius frequently show him together with geese.

Informed of the miracles the bishop had performed during the journey, Vigilius was eager to meet him. According to tradition, this was the only occasion that a Pope descended from the papal throne to meet a visitor. Vigilius asked to join Cerbonius at his dawn celebration and witnessed the miracle of an angel choir singing the Gloria. As a result, he received permission to continue his practice of early mass and returned to Populonia with honour.

Encounter with King Totila

When the Ostrogoths under King Totila invaded Tuscany, Cerbonius was arrested. They accused him of hiding several Roman soldiers in his house. Totila ordered him thrown to a ferocious bear in the Campo del Merlo, and looked forward to enjoying the show. He had a surprise coming, however.

Rearing up before the bishop, the bear suddenly became almost petrified, with its forelegs raised and jaws wide open. Then, slowly, it fell down onto its paws and began to lick Cerbonius’s feet. A public outcry forced Totila to release the bishop.

Lombard attack

After imperial forces under Belisarius repelled the Goths, the Lombards attacked from the north. Cerbonius had to flee again by sea and took refuge on the island of Ilva (Elba), which was still controlled by the Byzantines. He lived a very simple life in a cave.

Seriously ill and realising he would soon die, Cerbonius asked his friends to bury him in his beloved Populonia. They were afraid Lombard troops might capture them, but he assured them they would not have any problems if they buried him hastily and came straight back.

Laid to rest

Cerbonius died on 10th October 575. His companions set off immediately with his body in a boat. During the crossing, the sky darkened and a raging storm broke out. This completely hid the boat, which could thus slip unnoticed into the bay of Baratti below Populonia. Not a drop of rain reached it. A thick fog prevented the Lombard patrols from detecting the friends, and they buried the bishop near the shore. They returned to Elba on a sea as smooth as silk, and that same night the Lombards conquered Populonia, as Cerbonius had foreseen.

At his burial place, legend has it that a spring burst forth, which was later called “San Cerbone”. A proverb, still remembered by the people of the area, states: Chi non beve a San Cerbone – è un ladro o un birbone (“Whoever does not drink from [the fountain of] Saint Cerbonius – is a thief or a rascal.”)x

At the site of a chapel commemorating the saint’s life, near his cave, a remarkable fig tree, known as Fico di San Cerbone, grew. It produced fruit very late, around the anniversary of Cerbonius’s death (10th October).

A 1993 renovation restored the hermitage to its present state after it had fallen into disuse.

Taking liberty

I compiled this account of the life of Cerbonius from the sources listed below, which concur in most points. In my book, Aquila, I have slightly altered or added to the documented history, as follows:

- I have imagined Cerbonius’s father to have been a harsh businessman, who drove his son relentlessly, resulting in him leaving home at age twenty.

- I gave Cerbonius a wife and a son. No absolute rule of clerical celibacy existed at the time. Priests and bishops could live with a wife they had married before ordination. Some Church leaders argued, however, that they should thereafter abstain from intimate relationships.

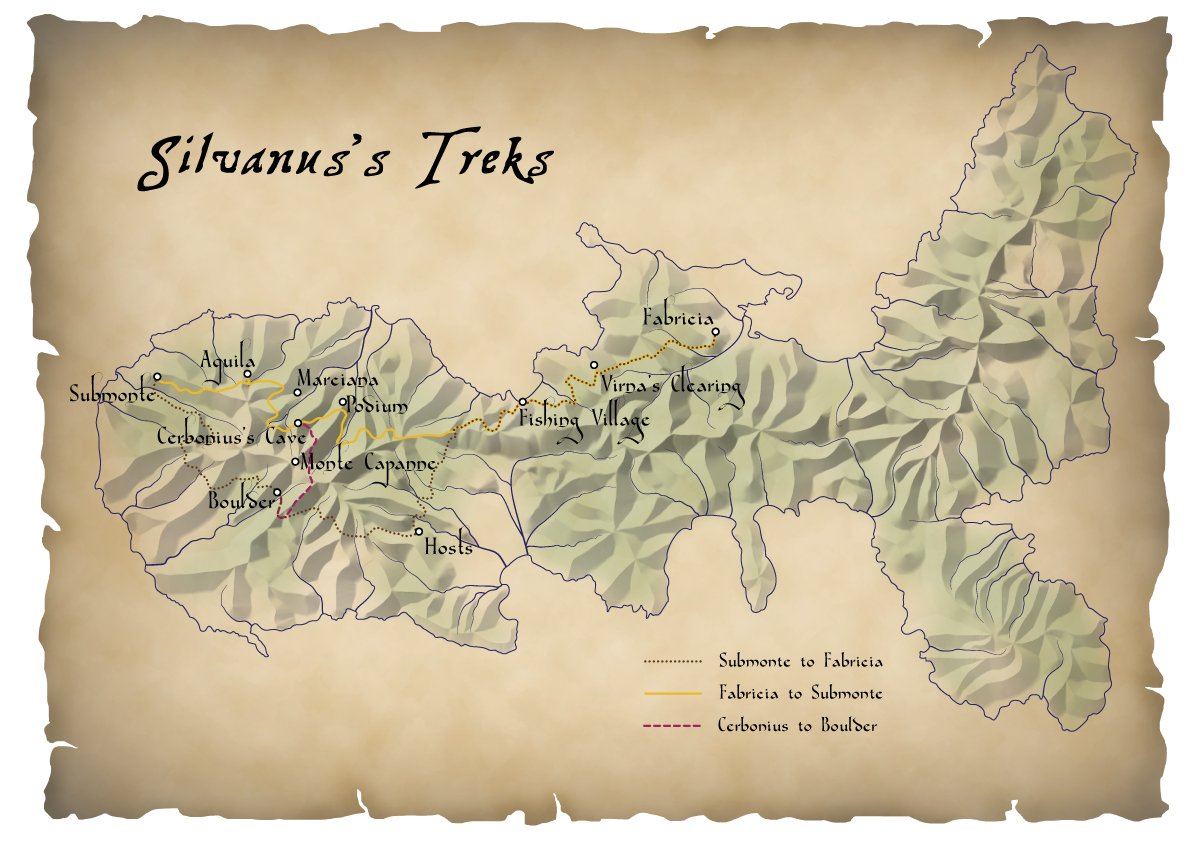

- Some accounts suggest Cerbonius fled to Elba immediately after the incident when Totila cast him to the bear (546 AD), and that he lived there for almost 30 years. The most reliable sources, however, say he only went into exile when the Lombards attacked in 573 AD, and thus lived only about two years on the island. In order for my imagined relationship between Silvanus and Cerbonius to develop over several years, I have had Cerbonius take up residence in the cave in about 567 AD.

The ‘Grotta di San Cerbone’ above Marciana Alta is currently too small to imagine that Cerbonius could have lived there for years, as legend has it. I assume it used to be much larger and has partially collapsed over the centuries.

The ‘Grotta di San Cerbone’ above Marciana Alta is currently too small to imagine that Cerbonius could have lived there for years, as legend has it. I assume it used to be much larger and has partially collapsed over the centuries.- Little is recorded of Cerbonius’s life on Elba. I have portrayed him as a well-loved, jolly old man with a deep, lively faith in his Friend Jesus. I assume he had a deep understanding of nature, astronomy and philosophy. He worships God in song and prayer, studies the Bible and other writings, teaches his disciples how to follow Jesus. He also cares for the needy in town, arbitrating with fairness and justice in matters of dispute.

- Following on from the incident in which Cerbonius tamed wild geese on his way to report to Pope Vigilius, I have him enjoying the company of two divinely assigned guardian geese while living in his cave.

- In 333 AD, Emperor Constantine ruled that a bishop could hear a lawsuit rather than a secular judge, and that judicial decisions made by bishops were valid. Julian later abolished this episcopal privilege, but Emperor Justinian reinstated it in 539. I envisage Cerbonius exercising this right to judge civil cases.

References:

- Cerbonius: (wikipedia)

- Gregory the Great, Dialogues

- Saint Cerbonius of Populonia (Italian)

- Santi e Beati (Italian)

- Den hellige Cerbonius av Piombino (Norwegian)

- Cerbonius von Populonia (German)

- Cerbonius (German)

- Synoptika, by Silvestre Ferruzzi (Lisola Editrice, 2008) (Italian)

- Constantine and the Bishops: The Politics of Intolerance, by H. A. Drake

I didn’t realize the Cerbonius in your story was based on a real person. I like your rendition of him in your novel. 🙂

Thanks for the feedback, Rebecca