H is for Huguenots – Devout Protestants

A contribution to the #AtoZchallenge 2024

What made Huguenots special?

The Huguenots were devout Protestants, who followed the teaching of the theologian, John Calvin. They emphasised salvation by faith in Jesus alone and the authority of Scripture. Their places of worship – referred to as temples rather than churches – were deliberately plain, lacking the ornate decorations and images of saints common to Catholic churches. Huguenots rejected the special status of priests, the authority of the Pope, and the veneration of saints, as well as all prayer or worship addressed to the Virgin Mary.

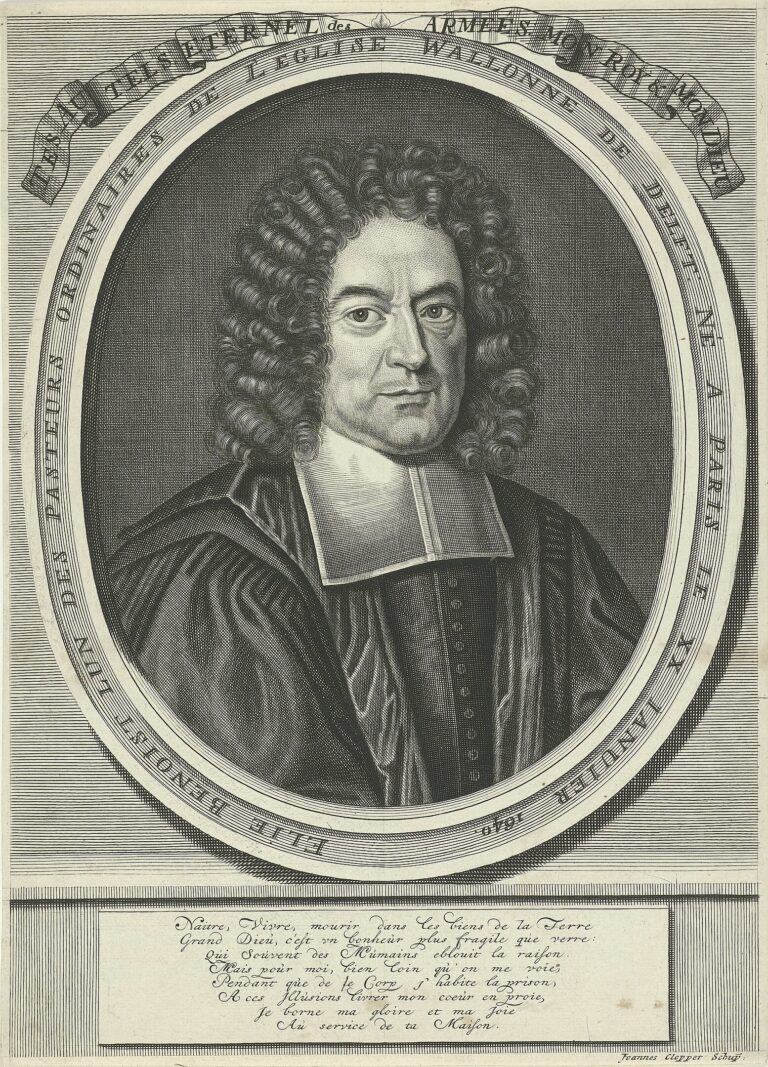

Their emphasis on everyone being able to read the Bible for themselves, meant Huguenot children attended school. In consequence, Huguenots often pursued careers in the professions, including law, medicine, education, trade and the clergy; others were skilled craftsmen. The exodus of Huguenots from France due to persecution resulted in the country losing a crucial group of educated individuals.

Why are they called Huguenots?

The name Huguenot has an uncertain origin. It began to be used around 1560. It may be derived from the German word “Eidgenosse”, meaning “confederate” and used to denote that believers were bound by oath in a confederacy together.

What secret symbols did the Huguenot use?

The méreau was a coin-like token that identified the holder as a confirmed Huguenot and authorised him or her to receive communion.

The Huguenot cross only came into use after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

In the book ‘Greet Suzon for me‘, Gédéon’s father Samuel makes use of several covert signs. Greeting a prospective colleague by shaking hands in a particular way, then gripping each other’s lower arm, if reciprocated, confirmed the other as a fellow believer. As he was being arrested, Samuel energetically rubbed his hands together – ‘frotter‘ in French – thus instructing his son to take the family to the de Frotté château, where he had arranged safe accommodation. And to understand what he meant by ‘Greet Suzon for me’, you’ll have to read the book.

What were the characteristics of a Huguenot service?

The design of their temples reflected the Huguenot belief in the supreme authority of the Bible. Accordingly, the congregation sat around the central pulpit and communion table, on which lay an open Bible. Decorations were limited to a simple cross and selected Bible verses on wall plaques. See Visiting a Protestant temple.

Replacing the ‘unscriptural and suspiciously pagan’ Catholic Mass and its Latin liturgy, a Huguenot service – known as a culte, and all in French – included prayers, a lengthy sermon consisting of biblical exposition, and communal a cappella singing of Psalms, in unison. (Organs were introduced later.) Members were expected to know the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer and the Apostles’ Creed by heart.

The Lord’s Supper was celebrated four times each year. Of the traditional seven sacraments of the Roman Church, only two were acknowledged: baptism and the Lord’s Supper or Holy Communion. Children were taught the Catechism.

Family religious practice in homes was based on Bible reading and the singing of Psalms, often in four-voice harmony and accompanied on a psaltery. See also: Protestant-music.

What was the function of a Huguenot minister?

The leader of a Huguenot temple was called a pastor.

Unlike the Catholic priests, pastors were not consecrated; they didn’t perform rituals but communicated God’s Word. Thus, their theological and biblical training was paramount, and their first task was to preach. Preparing several sermons a week took up most of their time.

Teaching catechism was their second task. For Sunday afternoon services, which attracted both children and adults, the pastor used Calvin’s catechism.

Pastors did little visiting, except to the sick and the distressed. The elders in the consistory visited members of the congregation and, together with the pastor, watched over their behaviour. See The Pastors.

Where were the Huguenot theological academies?

The synods of the Reformed Churches undertook the training of pastors, encouraging churches to open colleges and universities or academies (after the model of the academy founded by Calvin in Geneva in 1559):

- Nîmes: founded in 1561; closed in 1664 and taken over by Jesuits

- Orthez: 1566-1620

- Orange: 1573; closed in 1686 after dragonnades

- Sedan: 1579-1681

- Montpellier: 1596 until merged with the University of Nîmes in 1617

- Montauban: 1579-1685

- Saumur: 1599-1685.

Thus, the last of these academies were closed in 1685, after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. See The-reformed-academies.

How was the Huguenot church structured?

Ecclesiastical jurisdiction was relatively autonomous from civil jurisdiction. It was based on a representative structure in which laymen and pastors shared equal powers. At the local level, it comprised consistories and at the regional or national level synods.

Each local church had a consistory led by the pastor, which included the elders and deacons. It controlled beliefs and morals.

- Pastors preached. They were to proclaim the Word of God, administer the sacraments and exercise fraternal discipline together with the elders.

- Elders had the controversial duty of watching over the life of each person in a particular neighbourhood, admonishing in a friendly manner those at fault, and administering fraternal discipline. They visited every household in that area annually.

- Deacons cared for the needs of the poor and any members of the congregation who were in distress.

Beyond the local congregation, an elaborate hierarchy of colloquies, provincial synods and the national synod existed.

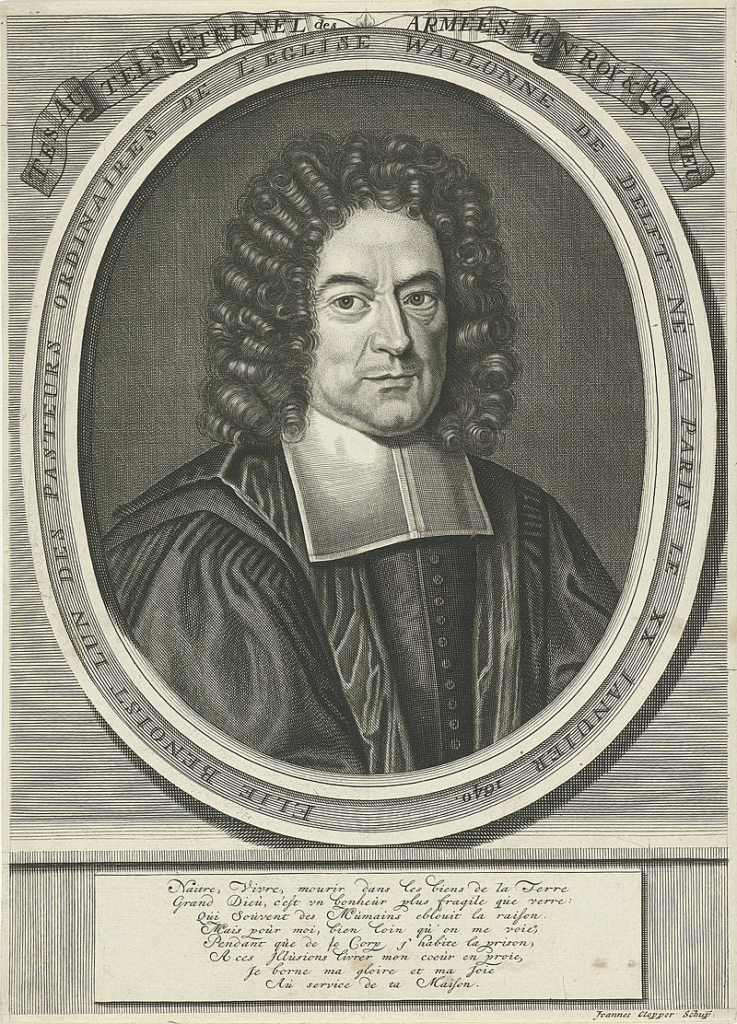

Who was the leader of the Huguenot church in Alençon in 1680?

Élie Benoist (20 January 1640 – 15 November 1728) studied theology in the Huguenot Academy of Montauban, until the Jesuits disbanded it. In 1665, he was called to Alençon, although the original Huguenot temple there had been demolished the previous year. For 20 years he served as pastor in Lancrel, on the outskirts of the city, with both prudence and competence, under the watchful eye of the authorities. He married a difficult wife and met with much opposition from the Roman Catholics, especially from the Jesuit Père de la Rue, who attacked him and even incited a riot against him in August 1681.

Benoist was already in hiding in Paris at the time of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. He immediately went to the United Provinces, and became the minister of the Walloon church in Delft. He later became famous as a historian of the Edict of Nantes.

Huguenot refugees

In English, the word refugee was first applied to French Huguenots who fled persecution in their native country after the revocation (1685) of the Edict of Nantes.

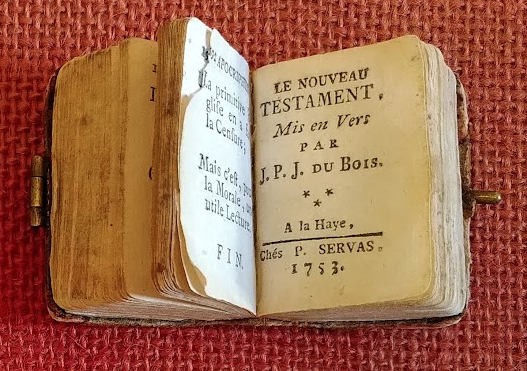

French Huguenots’ exodus to Protestant countries to escape persecution was a crucial event that spanned a century. The “First Refuge” in the 1560s peaked after the Saint-Bartholomew’s Day Massacre; the “Great Refuge” took place after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Over 200,000 Huguenots went into exile.

Why did Huguenots flee France?

Louis XIV acted increasingly aggressively to force the Huguenots to convert to Roman Catholicism. At first, he sent missionaries, backed by a fund to reward converts financially. Then he imposed penalties, closed Huguenot schools and excluded them from favoured professions. Escalating the pressure, he instituted dragonnades, in which military troops occupied and looted Huguenot homes, in an effort to force their owners to convert. In 1685, he revoked the Edict of Nantes, thus declaring Protestantism illegal.

The revocation forbade Huguenot cultes, prohibited emigration, and required children to be educated as Catholics, some of whom were kidnapped and confined in convents. This persecution proved both disastrous to the Huguenots and costly for France. It precipitated civil bloodshed, ruined commerce, and resulted in the illegal flight from the country of hundreds of thousands of Huguenots, many of whom were intellectuals, doctors and business leaders. Their skills were highly appreciated in their host countries.

How did they go?

From the North and West of France, many fled in rowing boats, to be picked up by waiting English, Dutch or Danish ships anchored offshore. The ships left with a few official passengers, such as pastors, but mostly with clandestine travellers, in terrible conditions down in the holds, after they had paid smugglers handsomely.

From the South, most people embarked in Marseilles or Nice for Genoa, and then travelled overland to Turin and finally north to the safe haven of Geneva. Huguenots from the Eastern parts mostly went by land. Journeys came up against natural obstacles, such as the bitterly cold Alps and Jura mountains, and the rivers Rhone and Doubs, which had few bridges. Surveillance was intense, but “with money you can cross anywhere”, as a boatman testified.

Where did they go?

The French term Le Refuge is used to designate all the countries that welcomed the French Reformed who fled France because of persecution.

Following the first persecutions, many Protestants from Normandy and Poitou took refuge in England and the Channel Islands. The United Provinces welcomed the greatest number, and Calvin’s Switzerland saw the passage of many refugees en route to German-speaking countries, especially Brandenburg, which practised a real policy of hospitality.

On arrival in a friendly host country, many such refugees expressed their overwhelming gratitude. For example, when Anne de Guelle made her will on 30th January 1707, she began it by identifying herself as:

a refugee on this island of Jersey for the reformed religion, recognising in all humility the mercy of God in having granted me an asylum in which I could finish my days in the open and free profession of the pure religion…

Jersey Archive D/Y/A/3/69, quoted in “Huguenot Research in Jersey” by Robert Nash and published in the Journal of the Channel Islands Family History Society, Volume X, Number 153, January 2017.

But Europe was not the only hospitable area. Indeed, many Protestants fleeing France took part in the conquest of the New World, a few went as far as South Africa. The countries to which the – often highly qualified – Huguenots fled usually welcomed them, and the economic, cultural and demographic contributions they made proved invaluable.

See The Huguenot Refuge.

Famous Huguenots

Springing from their devout faith and disciplined lifestyle, many Huguenots left their mark on history in areas such as literature, science, history, theology and the arts. Here are some of the better known:

- François Rabelais (1494-1553): author of the satirical novel Gargantua and Pantagruel, a landmark work of French Renaissance literature.

- Jean Calvin (1509–1564), author of Institutes of the Christian Religion, and founder of the Huguenot movement, together with William (Guillaume) Farel (1489–1565), who brought Jean Calvin to Geneva, and Théodore de Bèze (1519-1605), who succeeded him.

- Gaspard II de Coligny (1519-1572), a French nobleman and admiral, leader of the Huguenots during the French Wars of Religion. He played a significant role in advocating for Protestant rights and military strategies during the conflicts.

- Henry IV of France (1553-1610), earlier known as Henry of Navarre, a Huguenot leader. He converted to Catholicism for tactical reasons after becoming king of France and issued the Edict of Nantes in 1598, granting religious tolerance to Protestants and effectively ending the French Wars of Religion.

- Agrippa d’Aubigné (1552–1630), a French poet and historian; grandfather of Françoise d’Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon, who became the second wife to King Louis XIV.

- Denis Papin (1647–1713), the inventor of the pressure cooker and an early type of steam boat.

- Pierre Bayle (1647–1706), a philosopher and historical critic; a forerunner of the Age of Enlightenment through his emphasis on tolerance.

- Elie Benoist (1640–1728), the celebrated historian of the Edict of Nantes and pastor of the Alençon temple.

- Marie Durand (1711–1776), the most famous prisoner of conscience in the Tower of Constance, remembered for her personal letters.

- Isaac Watts (1674–1748), an influential Protestant author and prolific hymn writer, who helped usher in a new era of English worship.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), a Swiss writer, philosopher, social and educational theorist, descended from a Huguenot wine merchant, who later adopted an unorthodox form of Calvinism.

‘Greet Suzon for me’, a book about a Huguenot family’s perilous escape from France to Jersey, will be published in 2025.

Here are all the A-Z posts: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z