G is for Galley slaves – Never to return

A contribution to the #AtoZchallenge 2024

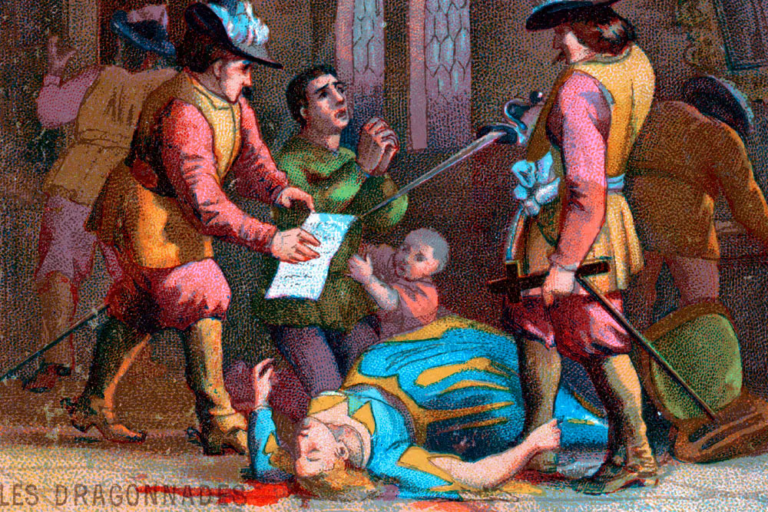

After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by King Louis XIV in 1685, the Huguenot faith was banned in France. Everyone had to accept the Catholic faith and attend mass. Whereas women who refused to abjure their Protestant faith could be imprisoned, e.g. in the infamous Tour de Constance, male recusants were often condemned to serve as galley slaves. The Musée du Désert in the south of France has amassed over 2,700 biographies of such slaves, most of whom never returned home alive.

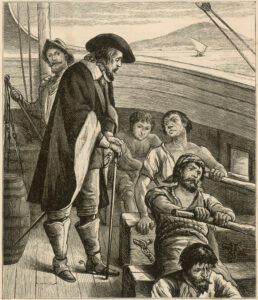

The men would be forced to row long oars in unison at the command of the master. They were often fed little and whipped or beaten when they could not perform to the satisfaction of the master.

What exactly is a galley?

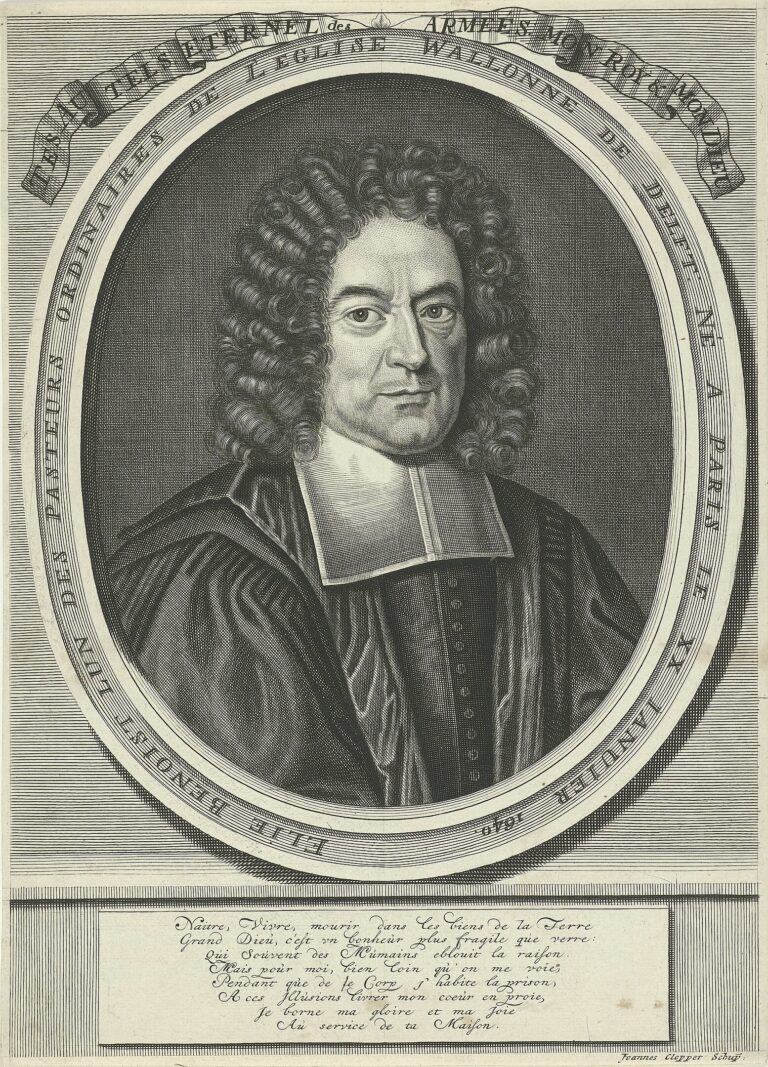

John Bion, a former Catholic chaplain of the galley Superbe, who later converted to Protestantism, describes these vessels.

A galley is a long, flat, single-decked vessel, though it hath two masts. They make use of the oars, because they are not able to endure a rough sea; and therefore their sails are for the most part useless. There are five slaves to every oar; one of them a Turk; who being generally stronger than the Christians, is set at the upper end, to work it with more strength. Generally, in all, there are 300 slaves; and 250 men, either officers, soldiers, seamen, or servants. There is, in the stern of the galley, a chamber shaped on the outside like a cradle, belonging to the captain: and solely his, at night or in foul weather; but in the daytime common to all officers and the chaplain. The rest of the crew are exposed above decks, to the scorching heat of the sun by day, and the damps and inclemencies of the night. There is a kind of tent suspended by a cable from head to stern, that affords some little shelter: but only in fair weather when they can best be without it. The least wind or storm it is taken down; the galley not being able to carry it for fear of oversetting.’

John Bion

A unique account of life as a galley slave

After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, the Huguenot Jean Marteilhe of Bergerac attempted to escape to the more sympathetic Protestant countries bordering France. Heading through the Ardennes towards Charleroi, he was captured by French dragoons and condemned to serve in the French Mediterranean galleys.

Marteilhe’s racy account represents the only authentic record of the miseries of a galley slave who experienced all the horrors of whips and chains and the dreaded bastinado – foot whipping. For six years he pulled his oar, often seeing friends and co-religionists lashed – sometimes to death – under the whips of the overseers, before being released in 1713.

Initially, upon capture, the slaves would be shackled together in what were termed ‘galley chains’. On all the roads of the kingdom, these miserable wretches might be seen, burdened by heavy chains … Sometimes sinking to the ground with exhaustion, but being compelled to rise by blows from the guards. Their food was unwholesome, and insufficient – for the guards pocketed half the amount allowed. At night they lay upon the bare earth in foul dungeons or barns, without covering, weighed down by their chains.

Galleys were also a secure means of incarceration, as well as potentially a means of religious conversion. Galleys provided a conveyor belt from the jails to the grave of free labour, and so relieved the pressure on what rudimentary prison system was then in place. Very few came back from the galleys because there was no one appointed to monitor the length of sentence served. Although a prisoner’s time might be up, his number was never called and, generally, once aboard, captives were there to die.

Galley Slave, by Jean Marteilhe

How much does your faith mean to you? Would you be willing to go through such horrendous torture rather than giving up your particular understanding of how you think God wants you to worship Him?

In the book ‘Greet Suzon for me’, Gédéon’s Huguenot father is arrested and sent to work as a galley slave. The rest of the family undertakes a perilous escape from France to Jersey. The book will be published in 2025.

Here are all the A-Z posts: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z