Shipwreck on Écréhous

A chapter from ‘Greet Suzon for me’

This draft of chapter 22 contains some drama, a style of prose I’m not good at. I’d appreciate any feedback – harsh or complimentary – to help me improve it.

Chapter 22

We were left to ourselves, facing a whole new life.

###

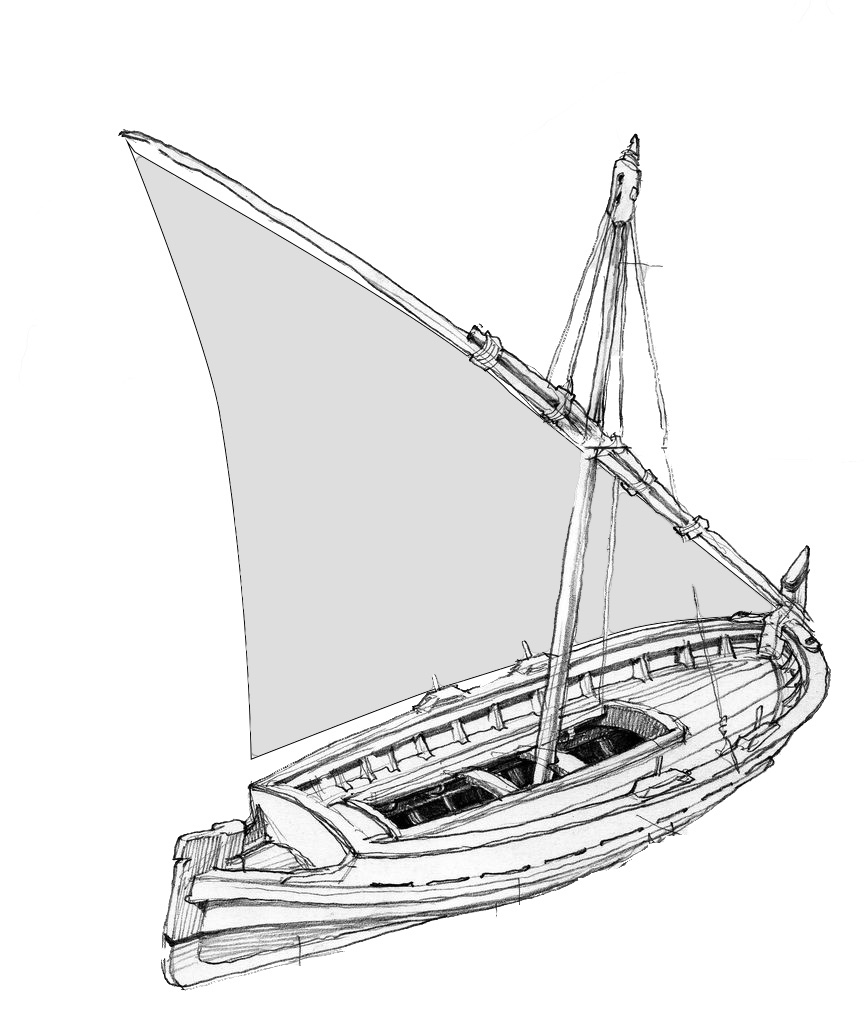

Stéphane turned the boat seaward and rowed out beyond the headland, which till then had offered protection from the southwesterly wind. Then he stowed the oars.

“Hold the tiller, Gédéon, while I trim the sail.” I took over from him in the stern and watched as he pulled on some ropes that tipped the point of the yard from which the triangular sail hung. “Keep your heads down, ladies!” he shouted, as the wind suddenly caught the sail and flung it to starboard.

“There’s a strong current from the tide sweeping us northwards,” Stéphane explained, pointing out what he meant with his hand. “Jersey is over to the west and the prevailing wind is from the south-west, so we’ll be sailing into the wind.”

What exactly did that mean?

We soon found ourselves in much rougher water. The little oil lamp swung to and fro from a hook on the mast. I again felt nauseous, and soon Maman threw up over the side. When I noticed Madeleine was also about to vomit, I struggled through the bags and legs to help her sit up. Stéphane took in the situation at once, took over the tiller and pointed to an iron pail in the hold, which I was able to grab just in time. Madeleine emptied last night’s meal into it, then tried to spit out the foul-tasting remains. Someone pressed a gobelet of water into my hand, with which I helped the poor girl to rinse out her mouth. Thank God, the Morins had thought to stock some basic supplies for the journey in the boat.

I watched, fascinated, as Stéphane wetted his finger and held it up to sense the direction of the wind. He kept looking up at the little ribbon tied to the top of the mast and often gazed down at the water. I tried to learn his tricks as we tacked back and forth through the night.

Storm

After about an hour, the wind rose and the boat began to pitch, making us grasp onto anything we could hold. As I looked out at the churning waves, my heart sank. When we went lobster fishing last year, it was calm. But now a storm was brewing and the sky hung low and ominous over us like a dark shroud.

Suddenly, a brilliant bolt of lightning streaked across the sky, illuminating the clouds in a blinding burst of white light. The thunder that followed sounded like a cannon, jolting us all and shaking the boat to its very core. Maman looked up at me with terror-filled eyes and grabbed my arm, her fingers digging painfully into the flesh.

Madeleine curled up on the deck next to the escritoire, her thin frame trembling, and tried to pull the blanket up. “Oh, Jesus!” she cried. “You didn’t abandon your friends in the storm. Help us now.”

What faith she had!

At the tone of her plea, Fidel made his way shakily over to her and licked her face. She hugged him, then stroked his neck.

A huge wave crashed over the bow, drenching us all in salty spray. Maman screamed.

Stéphane fought against the elements. His muscles bulged as he strained against the tiller with all his might. Sweat poured down his face. His eyes were locked onto the sail, which he attempted to control by pulling and loosening various ropes – sheets, he called them – in a desperate attempt to keep the vessel steady and on course in spite of the relentless onslaught of wind and waves.

A sudden gust threw the sail across to port. It hit me so hard I fell to the deck, stunned for a moment.

“Sorry.” Stéphane’s voice was barely audible above the roar of the elements. “The wind is playing tricks on me.”

He battled on for what seemed like hours. At each tack, the boat pitched precariously and the sail slapped from one side to the other with a sound like a gunshot. Alarming creaks came from somewhere near the top of the mast.

Too much!

“Come here, Gédéon,” Stéphane yelled. “I can’t manage like this any longer. The gale is too strong. I need to take the sail down, if we want to make it out alive.”

I scrambled aft to join him. “What should I do?”

“Hold the tiller right over, like this.”

I nodded, took over from him, amazed at the force it needed, and watched as he tugged at the ropes.

“They’ve got tangled,” he shouted. “I’ll have to climb up the mast.”

Without anyone controlling the sail, it flapped around wildly and the boat tilted over dangerously. Maman cried out in panic.

“Slacken that sheet!” Stéphane screamed.

I fumbled for a rope, without letting go of the tiller.

“No! That one!” he shouted, pointing to a different one. “Let it out slowly. And pull the other one in.”

I undid the rope from its cleat and could barely control it as the wind brought the tip of the sail round. Slowly, the boat righted itself. Stéphane began to shin up the mast, his legs gripping the wet wood with difficulty. But the halyard – I was learning new words all the time – had tied itself in a knot; he wasn’t able to release it.

“I’ll need to cut it down.” Alarm sounded in his voice, “or we’ll capsize. Do you have a knife?”

How could I reach my knapsack without leaving my post at the helm?

“Maman,” I shouted. “Take my knife from the knapsack and pass it to Stéphane!” I wasn’t in the habit of giving her orders – nor she of taking them from me – but our plight was desperate. She didn’t argue. She found the knife among my other treasures and crawled toward the mast.

Just as Stéphane reached down to take it from her, a terrifying crack resounded. We looked up in horror. The yard had snapped just above where it was attached to the mast. The top section folded over, causing half the sail to drop over us.

“Oh, Lord, help us!” Madeleine cried in a hoarse voice.

My sense of dread grew stronger with each passing moment. How were we going to get anywhere without a sail? The boat heaved and swayed. Waves splashed over the bulwarks and the hold began to fill with water.

I had an idea

I began to scoop bucketfuls out over the side, but kept peering at the remains of the sail, pondering. I passed the pail to Maman, who understood what was expected of her and went into action as best she could. Then I fumbled in the hold for a coil of rope.

Taking a deep breath, I took the knife from Stéphane, who peered at me with a questioning look. I must have looked like a pirate, with a dagger clamped between my teeth and the rope over my shoulder. Gingerly, I began to climb up the mast myself. I had an idea.

Locking my legs and one arm around the swaying pole, I began to cut along one of the reinforcing seams of the sail. Would this work? The sail was wider than I had realised and it proved difficult to cut all the way to the edge. At last I managed. I still had to saw through the remaining splinters of the snapped yard, and then discarded the top section and the useless part of the sail into the sea. With the rope I secured the remaining section of the yard to the mast and clambered down, trembling from the strain.

“Release both sheets,” I called. Stéphane, peering in wonder at my action, did as I said. What was left of the yard hung down alongside the mast. I grabbed the new edge of the sail, crawled out onto the bowsprit and tied to its tip. “Half a sail should be better than none,” I called back.

After some experimenting, we were able to swing the hanging yard to port or starboard, and so we regained a limited control of the vessel. The worst of the storm seemed to be over, although the waves were high and gusts of wind kept taking us by surprise.

The tide turns

Stéphane again peered down at the sea for some moments. “The tide is turning,” he announced. “It must be about four o’clock.” How can he know that? Neither stars nor land was in sight. “We’ll continue to head into the wind as much as possible, but I can’t be sure how far the storm has swept us off course. We’ll see when it gets light.”

The night was long and both Stéphane and I were tired, our muscles quivering from over-exertion. Maman found some hard sea biscuits in a box the Morins had provided. She passed them around, along with a gobelet of water. That was most welcome. Then she replenished the oil in the lamp.

I went over to ask Madeleine how she was.

“Very weak,” she said, “but happy. And confident.” Her face seemed to be shining.

“Confident?” I felt her forehead. She was still feverish.

“Jesus is with us. Just like He was with His friends on the Lake of Galilee. He promised me he would bring us safely to land.” She squeezed my hand. “Just trust Him, Gédé!”

‘Just trust Jesus!’ she says. Why haven’t I got faith like hers? We are going through this traumatic flight, and I’m not even sure I believe in our cause. Wouldn’t it have been easier just to comply with the priest and the intendant – attend Mass and pretend to pray to Mary – instead of suffering this ordeal?

Shipwreck

A sudden jolt shook the boat, accompanied by a horrible grinding sound. What was that? My heart thumped in my chest.

Stéphane sprang to the bow and looked over. “We’ve hit a rock!” He came back and looked down the hatch. Terror showed on his face. “We’re holed!”

The boat shuddered and groaned, buffeted by the waves, but apparently stuck fast on an invisible reef. Would it break apart? Bit by bit the stern settled lower as the hold filled with water. Our feeble attempts at scooping it out seemed to make no difference. How long before we sank?

The scraping and cracking sounds continued. Even Stéphane shook his head in consternation.

Madeleine sat up and began to pray. “O Lord, I thank You that You are here with us. Thank You that we are all alive and well.” – Well? But she’s sick. – “Please give us a sign to assure us You haven’t abandoned us.”

As if in answer, two things happened. A gap appeared in the cloud cover to reveal a hint of light in the East; and a plaintive ‘yeow’ cry made us all gaze heavenwards. Madeleine laughed. “Oh, thank You, Lord.”

A gull swooped around the boat. Soon a second one arrived. “That’s a sign there’s land nearby,” Stéphane remarked. “Probably Les Écréhous.”

“Where’s that?”

“Little islands – hardly more than rocks – between Carteret and Jersey. If we’re lucky, we can get ashore.”

That must be the cluster of small islands I saw from the hill that morning. Or, rather, yesterday morning. So much had happened in one day.

Slowly, the light improved, although it was long before sunrise. My eyes widened at the sight of jagged rocks emerging from the sea, and beyond them a grass-topped island with some man-made structure on it.

Stéphane’s voice snapped me back to reality. “It must be almost low tide. We have to get ashore now before these rocks disappear.” He had already pulled a long rope out from the water-logged hold and was tying it to the mooring rope. “You said you could swim, Gédéon?” I nodded and he thrust the free end of the rope into my hand. “This is about a hundred pieds long. Should be enough to reach that bigger rock over there. Then you can drag the boat ashore.” We stared at each other for a tense moment. “I suggest you take off your clothes. They would drag you down.” I must have looked uncertain and he grabbed my arm reassuringly.

“Go on, Gédé!” Madeleine’s cheery voice gave me courage. “You can do it.”

It wasn’t a question of ‘Did I want to?’ or ‘Was I willing to try?’ Their lives depended on me doing what Stéphane said.

Relief

I stripped to my breeches, tied the rope around my waist and gingerly stepped out of the boat into the cold, surging waves. The jagged rock hurt my feet, so I struck out and swam toward the nearby crag. The sea water did offer more buoyancy than I was used to from fresh water, but I wasn’t accustomed to the swell that lifted me up and down, dragging me first away from the shore, then nearer. I decided to cooperate with the movement rather than try to fight against it. Slowly, slowly, I got nearer. Shouts of encouragement from the boat spurred me on. Soon my hands felt rock. I dragged myself forward, scraping my knees, until I could stand, then climbed cautiously out of the water. The rope was just long enough.

Stéphane called over. “Can you tie it to the rock?”

I looked around. “I think so. Just a moment.”

“Good. Between us we’ll get the boat ashore before she sinks.”

A sudden splash took me by surprise. I could hardly believe my eyes. Fidel was swimming strongly toward me. “Good boy! “ I cried. The less weight left in the boat, the better.

With a mighty thrust from an oar, Stéphane managed to free the boat from the rock. It rode very low in the water, but floated. “Pull us in while I row,” he barked.

The ebb and flow of the waves meant the boat sometimes struck other hidden rocks and it was difficult to judge if we were succeeding or not, but soon I was able to wrap another loop of rope around the rock.

Fidel climbed out and tried to help.

As the boat got nearer and the eastern sky began to brighten, I was struck by Stéphane’s weathered face, set with determination. I hadn’t seen him in daylight since last year; he seemed much more mature than I remembered. What a great fellow he was!

With the excitement of the action, I hadn’t noticed how cold I was. Now it registered; shivering, I kept tugging until the boat reached my rock. From there to the grass-topped island wasn’t far, although it would mean everyone would have to wade from rock to rock.

Stéphane jumped out and checked that the rope was secure. Then he helped Maman to safety. She was trembling and didn’t say a word. I held her under her arm and led her through the shallow water across to the grass, then came back.

How would we get Madeleine over in her weak state? Without even a nod or a wink, Stéphane picked her up from the deck, threw her over his shoulder, then waded across to the rock, holding on to the rope with his other hand.

She laughed as he set her down. “Thank you so much.”

“I couldn’t believe how light you are,” he replied. “Just skin and bones. You seem to be wasting away.”

She chuckled. “I won’t be needing this body much longer.”

Puzzled by that remark, I put my arm around her and helped her over to join Maman.

Next came all our baggage and the supplies the Morins had given.

But what about Maman’s escritoire? That was still in the boat. And there it would have to stay – at least for the time being.

A bright day was dawning and we took in our surroundings. Grass with weather-beaten gorse bushes and the ruins of a building on the top of the mound. Gulls were circling overhead, screaming their sad song. Were they expecting us to feed them?